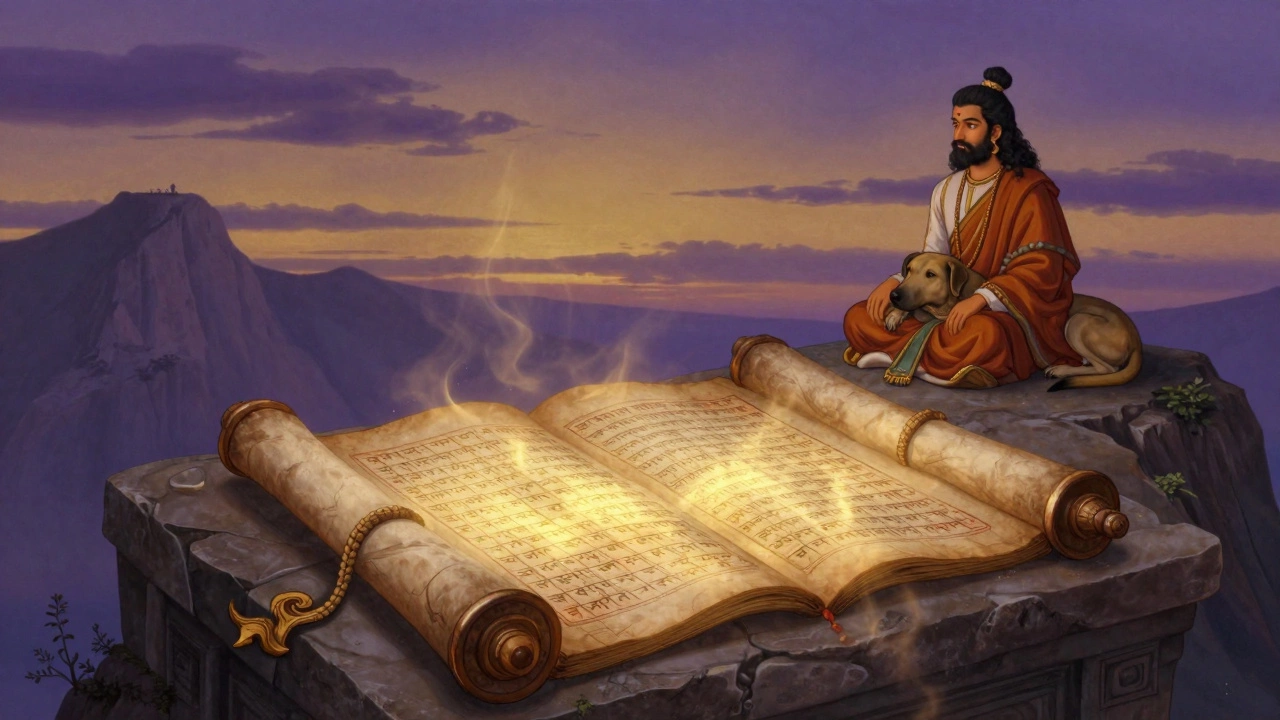

There’s no single epic poem in Indian literature that’s called "the epic poem about the depression"-but if you’re looking for a work that captures the weight of human suffering, loss, and inner collapse like no other, the Mahabharata is it. Not because it’s labeled that way, but because it doesn’t look away from despair. It holds it. It breathes with it. It lets characters sit in silence after everything falls apart.

Why the Mahabharata Feels Like a Poem About Depression

The Mahabharata isn’t a war story. It’s a story about what happens after the war ends. The battles are loud, but the silence afterward is louder. Yudhishthira wins the kingdom, but he doesn’t feel like a king. He walks through his palace like a ghost. His brothers are dead. His children are dead. His teacher, Drona, was killed by deception. His wife, Draupadi, lost everything she loved. And still, he sits. He doesn’t celebrate. He doesn’t smile. He just sits.

This isn’t drama. This is depression-not the kind you see on social media, but the deep, quiet kind that doesn’t cry out. It’s the kind that comes after you’ve lost so much you don’t even know how to miss it anymore. The text doesn’t say "Yudhishthira was depressed." It shows it. He refuses to eat. He refuses to speak. He tells Krishna, "I have no joy left. I have no purpose. What is the point of victory if it costs everything?"

That moment-right after the war-is the closest Indian literature ever came to writing a psychological portrait of emotional collapse. And it’s not just Yudhishthira. Karna, the tragic hero, dies alone, betrayed by his own birth, knowing he was loved by no one who mattered. Draupadi, who once laughed in courts and danced in palaces, spends her final years walking barefoot through forests, mourning. These aren’t characters. They’re survivors of emotional genocide.

Depression in Ancient Texts Isn’t Called Depression

There was no word for "depression" in Sanskrit. But there were words for shoka-grief that doesn’t leave. For vyatha-a dull, constant ache in the chest. For niruddha-chitta-a mind that’s locked shut, unable to feel joy or move forward.

The Mahabharata doesn’t treat these as weaknesses. It treats them as truths. When Arjuna freezes on the battlefield, trembling, unable to raise his bow, he’s not being cowardly. He’s having a breakdown. Krishna doesn’t tell him to "snap out of it." He doesn’t give him a pep talk. He gives him the Bhagavad Gita-a long, slow, brutal conversation about duty, loss, and the illusion of control. It’s not a solution. It’s a companion through the dark.

Modern psychology calls this existential crisis. Ancient India called it dharma. The same thing. When you lose meaning, you lose your way. The epic doesn’t fix it. It just says: Keep walking.

Other Indian Poems That Carry the Same Weight

The Mahabharata is the biggest, but it’s not the only one. In the 19th century, Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay wrote Devi Chaudhurani, where a woman becomes a rebel after her husband is killed by the British. Her grief turns to rage, but the rage doesn’t heal her. It hollows her out. She becomes a leader, but never a person again.

In the 20th century, Rabindranath Tagore wrote poems like "Shesh Lekha" (The Last Writing), where an old man writes letters to his dead wife, over and over, even though she can’t read them. He doesn’t cry. He just writes. That’s depression too. Not loud. Not dramatic. Just… there.

Even modern poets like A.K. Ramanujan and Kamala Das wrote about emotional numbness. Das wrote: "I am not a woman anymore. I am a wound that doesn’t bleed." That line doesn’t need context. It stands alone. It’s the sound of someone who’s been hollowed out by years of silence.

Why This Matters Today

In India, mental health is still whispered about. People say "you’re just stressed" or "pray more" or "be strong." But the Mahabharata doesn’t say that. It says: You don’t have to be strong. You just have to keep breathing.

When a young man in Pune sits alone in his room after failing his exams, and his family tells him to "stop being lazy," he’s not lazy. He’s carrying the same silence Yudhishthira carried. When a woman in Chennai stays quiet after her mother dies and no one asks how she’s doing, she’s living the same grief Draupadi lived.

Indian literature never gave us a simple answer. It gave us space. Space to feel broken. Space to sit. Space to not be okay.

The Real Epic Isn’t the War. It’s the After.

Most epics end with victory. The Mahabharata ends with ashes. The Pandavas walk into the Himalayas. One by one, they fall. Draupadi first. Then Bhima. Then Arjuna. Then Nakula and Sahadeva. Only Yudhishthira reaches the gates of heaven. And when he gets there, he’s told his dogs-his last living companions-are not allowed. He refuses to go without them.

That’s the moment. Not the war. Not the throne. Not the glory.

He chooses loyalty over heaven.

He chooses grief over salvation.

And that’s why this isn’t just an epic. It’s the most honest poem about depression ever written.

What You Can Take From It

You don’t need to be a scholar to feel this. You just need to have been alone in the dark. Here’s what the Mahabharata teaches if you’re carrying depression:

- You don’t have to be happy to be worthy.

- Surviving is not failing.

- Silence doesn’t mean weakness-it means you’re still here.

- Love doesn’t disappear just because you can’t feel it.

- Even the gods didn’t fix Yudhishthira. They just sat with him.

There’s no cure in this story. No magic pill. No quick fix. Just a man who kept walking, even when his legs didn’t want to move.

That’s the epic. That’s the poem. That’s the truth.

Is there a specific Indian epic poem titled "The Depression"?

No, there is no Indian epic poem with the title "The Depression." But the Mahabharata contains the deepest, most sustained portrayal of emotional collapse, grief, and existential despair in classical Indian literature. Its characters experience depression not as a disorder, but as a human condition-shown through silence, withdrawal, and loss of meaning.

Why is the Mahabharata considered a poem about depression?

The Mahabharata is considered a poem about depression because it doesn’t glorify victory-it lingers in the aftermath. Characters like Yudhishthira, Draupadi, and Karna show signs of emotional exhaustion, numbness, and loss of purpose after trauma. Their pain isn’t solved by gods or battles. It’s carried. That’s the essence of depression: not crying out, but enduring.

Did ancient Indians understand depression like we do today?

They didn’t use modern medical terms, but they recognized emotional collapse. Sanskrit had words like shoka (grief), vyatha (inner ache), and niruddha-chitta (a mind shut down). The Mahabharata and texts like the Charaka Samhita describe symptoms we’d now call depression: insomnia, loss of appetite, withdrawal, and detachment from pleasure. They didn’t call it a disease-they called it a part of being human.

Are there other Indian poems that deal with sadness?

Yes. Tagore’s "Shesh Lekha" shows a man writing letters to his dead wife. Kamala Das wrote, "I am not a woman anymore. I am a wound that doesn’t bleed." Bankim Chandra’s Devi Chaudhurani portrays grief turning into hollow strength. These aren’t sad poems-they’re honest ones. They don’t offer hope. They offer presence.

Why does this matter for people today?

Because it tells you: your silence doesn’t make you broken. Your lack of joy doesn’t make you weak. The Mahabharata doesn’t fix Yudhishthira-it lets him sit. It doesn’t cheer him up-it walks with him. That’s more healing than any quick fix. If you’re feeling empty, you’re not alone. You’re in the company of kings, warriors, and gods who felt the same.